When in their careers are artists most creative? Since the publication of Harvey Lehman's Age and Achievement in 1953, psychologists have contended that the answer depends on the artist's domain, or genre. So for example Lehman concluded that "the golden decade for the writing of secular poetry occurs not later than the twenties." In 1993, Howard Gardner wrote that "lyric poetry is a domain where talent is discovered early, burns brightly, and then peters out at an early age. There are few exceptions to this meteoric pattern." In 1996, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi agreed: "The most creative lyric verse is believed to be that written by the young." In 2004, James Kaufman declared, "Poets peak young."

|

The psychologists' analysis rests on the assumption that the creative life cycles of practitioners of a given discipline are homogeneous. Keith Sawyer stated this belief in 2006: "Every creative domain has its own inverted-U shape that tends to apply to all individuals working in that domain. Each domain has a typical peak age of productivity, the age at which the most significant innovation of a career is typically generated."

|

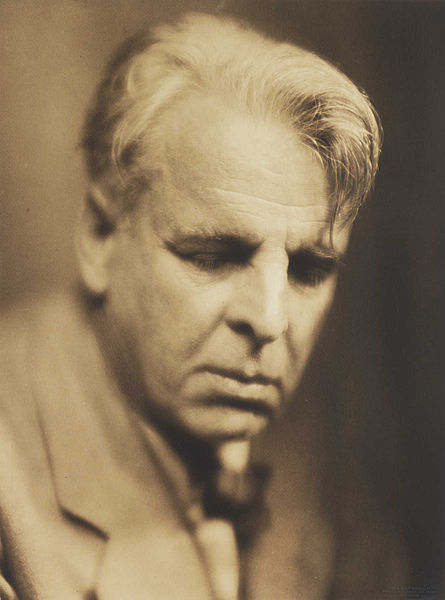

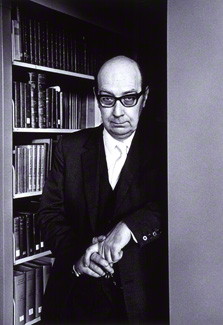

Do poets peak early? Apparent evidence that they do is provided by the striking list of poets who made major contributions in spite of dying young: Robert Burns, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Rimbaud, Leopardi, Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Hart Crane, Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath. Nor does this exhaust the roll of poetic prodigies. T.S. Eliot published "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" at 23, and The Waste Land at 34. Ezra Pound published his most frequently anthologized poem at 30, and Richard Wilbur his at 34.

The writers named above are all among poetry's young geniuses. They were all conceptual innovators, whose poetry tended to be abstract, introspective, formal, based on imagination. But they are only part of the discipline. For poetry also has its old masters. These are experimental innovators, whose art tends to emphasize observation, the specific, and the concrete, expressing the writer's perception of reality using vernacular language.

|

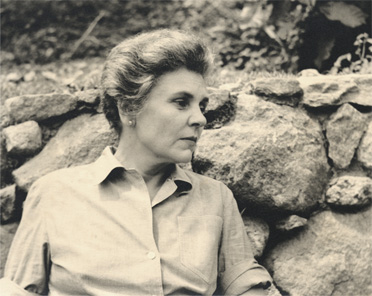

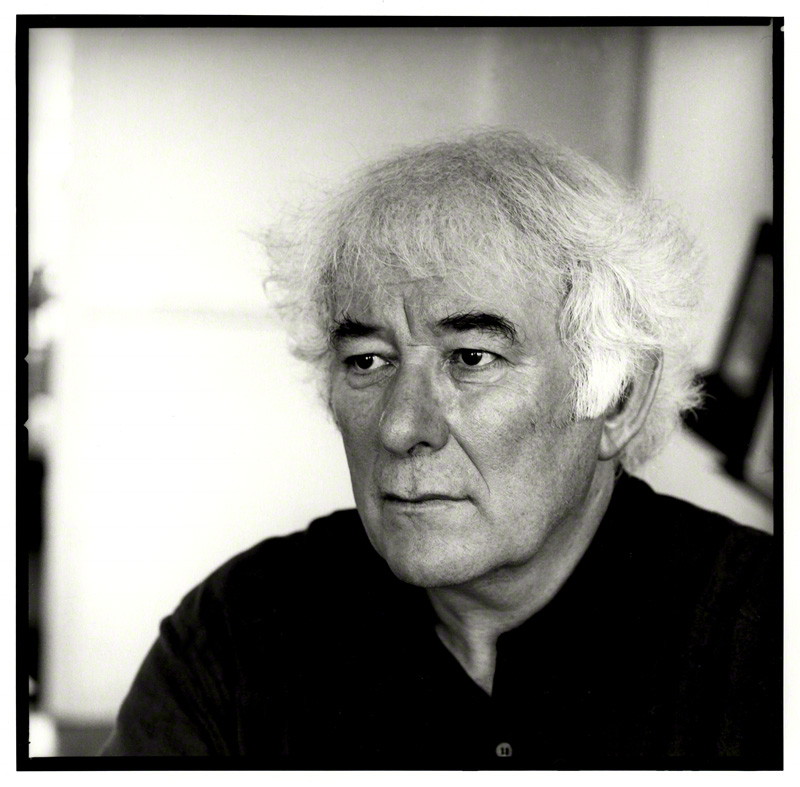

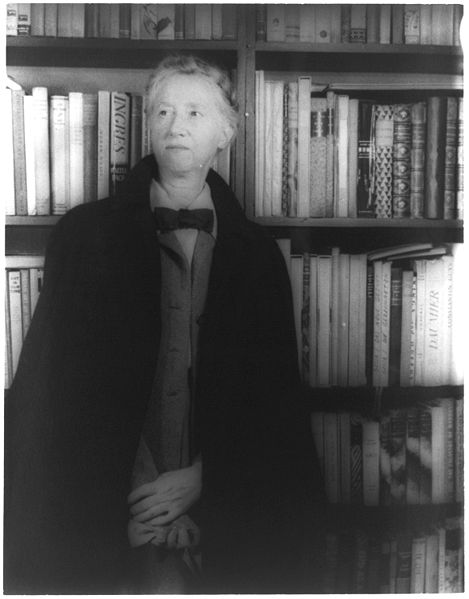

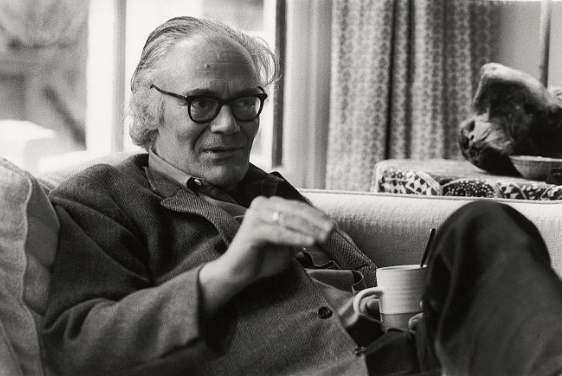

Experimental poets are typically late bloomers. Robert Frost published "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," his most anthologized poem, at the age of 48. William Carlos Williams published his two most anthologized poems at 40 and 59; Wallace Stevens his at 42 and 55; Robert Lowell his at 41 and 42. Elizabeth Bishop published the villanelle "One Art," her second most anthologized poem, at 65. Nor are these rare exceptions. Other modern experimental poets who were excellent late in their careers include Thomas Hardy, William Butler Yeats, Marianne Moore, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Penn Warren, W.H. Auden, Philip Larkin, Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, and Joseph Brodsky. These are not a few exceptional cases: they are in fact a substantial proportion of the major figures in modern poetry.

|

The difference in the life cycles of conceptual and experimental poets is no mere numbers game, but stems from basic differences in the nature of their art. Conceptual poets are brash, iconoclastic, and often transgressive, and are generally at their best before they become constrained by established habits of thought. In contrast, the greatest achievements of experimental poets depend on deep knowledge of their subjects and subtle mastery of language and style. Robert Frost believed that a poem "begins in delight and ends in wisdom." He contended that poets need a kind of knowledge that cannot be gained solely in libraries, or acquired deliberately, but comprises "what will stick to them like burrs where they walk in the fields." Randall Jarrell explained that Frost's greatest poems "come out of a knowledge of people that few poets have had, and they are written in a verse that was, sometimes with absolute mastery, the rhythms of actual speech." Frost wrote in his notebook, "I had rather be wise than artistic."

|

Conceptual innovations are often formulated and introduced suddenly and completely, and consequently are often recognized immediately as novel and revolutionary. Thus William Carlos Williams reflected that T.S. Eliot's Waste Land "wiped out our world as if an atomic bomb had been dropped on it," and the critic A. Alvarez recalled that when Sylvia Plath first read "Daddy" and "Lady Lazarus" to him, he was shocked: "at first hearing, the things seemed to be not so much poetry as assault and battery." In contrast, experimental innovations generally lack drama, and appear quietly and gradually. As a result, experimentalists are often appreciated only by experts. Thus the poet James Merrill praised Elizabeth Bishop's understatement and unpretentiousness: "her whole oeuvre is on the scale of a human life; there is no oracular amplification."

|

Experimental art is less likely that its conceptual counterpart to depend on sudden inspiration, and more likely to depend on extended reflection and revision. William Butler Yeats toiled for decades "to make my work convincing with a speech so natural and dramatic that the hearer would feel the presence of a man thinking and feeling." Seamus Heaney elaborated on the lessons of Yeats' extended experimental evolution: "What Yeats offers the practicing writer is an example of labor, perseverance. He is, indeed, the ideal example for a poet approaching middle age. He reminds you that revision and slogwork are what you have to undergo if you seek the satisfactions of finish...He proves that deliberation can be so intensified that it becomes synonymous with inspiration."

|

Wise, mature, and diffident old masters do not trumpet their own brilliance with the bravado of brash young geniuses, and the subtlety of their innovations often makes them less conspicuous than the bombshells of their conceptual peers. So perhaps it is not surprising that, as the poet Josephine Jacobsen observed, "in our general conception, old age is a period alien, if not fatal, to poetry." The simplicity of the idea is appealing. But scholars should be willing to sacrifice simplicity for accuracy. The truth is that all poets are not alike: the life cycle of creativity depends not on the domain, but on the approach of the individual. Jacobsen herself recognized that the poetry of Frost and Williams "reached its highest level when the men who produced it were able to speak from great reserves of experience." It is simply not true that the twenties is the golden decade of writing poetry, nor is it true that poets peak young. In fact, poetry has two very different life cycles of creativity: conceptual poets peak early, but experimental poets peak late. Understanding poetry - and creativity in general - depends on being able to comprehend this diversity among poets, as among practitioners of virtually every other intellectual activity.

via Books on HuffingtonPost.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment