Pages

Monday, September 30, 2013

I Know Who I Am and I Love What I Do

I know who I am.

I am one of eight children, born in Houston and a graduate of the Houston public schools.

I was lucky enough to be admitted to Wellesley College, where my friends included incredibly talented women.

I married a wonderful man two weeks after college, moved to New York City, and began having children. I had three sons, one of whom died of leukemia at the age of two.

I earned a Ph.D. in the history of American education from Columbia University in 1975. My mentor was the great historian Lawrence A. Cremin.

My first book was a history of the New York public school system, published in 1974. It was also my doctoral dissertation.

I was divorced in 1986. My ex-husband and I are good friends.

From 1991-93, I was Assistant Secretary of Education in the first Bush administration. Then I worked as a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution for two years.

I missed New York City and moved back to Brooklyn and became an adjunct at New York University. I published more books.

In 1997, the Clinton administration appointed me to serve on the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees federal testing. Secretary Richard Riley reappointed me in 2001, and I served on that board for seven years, learning a lot about testing.

I was a fellow at three different conservative think tanks in the 1990s and early years of this century. The Manhattan Institute, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, and the Koret Task Force at the Hoover Institution.

In 2010, I published a book explaining that the ideas I had thought were good in theory turned out not to work, that they were actually damaging education, and I became a critic of testing, accountability, choice, and competition. My book explained why and how I lost faith in these ideas. It is The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining American Education.

I have lived with my best friend for the past 25 years.

I still live in Brooklyn. I have written ten or eleven books and edited many more.

I have four grandsons.

My latest book -- Reign of Error -- is the #1 book in education and the #1 book on public policy as of this moment on Amazon.

This week I visited Denver, Seattle, Sacramento, and Berkeley. Tonight I speak in Palo Alto, then twice in Los Angeles. I have no staff, no secretary, no assistant. I am not funded by anyone.

I am 75 years old.

I love what I am doing.

I love children, and I admire those who dedicate their lives to educating children and improving the lives of children, families, and communities.

I want all children to have a wonderful education, not just the basics and testing.

I will work for a better education for all as long as I have strength and breath.

The Not-So-Happy Happy Hour

At work, socializing tends to be more conservative, as compared to if you and some friends were having a barbecue at your house. However, one aspect of workplace socializing that tends to be a grey area of proper behavior is the office happy hour.

Office happy hours are designed to create camaraderie amongst the team, but can also be a dangerous breeding ground for social snafus. During a happy hour, some coworkers forget they are still surrounded by managers or other colleagues, not their personal friends.

So before you head out to that next office happy hour, check out these three tips on how to put the happy back into happy hour.

Tip#1: Know Your Limit

I don't care if you work at the hottest bar in Las Vegas where your job is to get wild and wasted 24/7, there is always going to be a level of professionalism that even the craziest party animal shouldn't cross at a work function. I'm not saying you can't have fun, but acting properly at office events is not about being awkward or boring, it's about not becoming the topic of conversation at the water cooler the next day... or needing someone to drive you home because your face has been planted (and drooling) on the bar for an hour.

Everyone has their own alcohol consumption threshold, which is why it's absolutely crucial to know your limit and, more importantly, stick to it! This is not a time to show off how many shots you can do before you pass out. People tend to forget that it's still a work function and whether you like it or not, you are under the judging eyes of your colleagues. Some stick-in-the-mud may even report you to HR if you do something they consider inappropriate while three sheets to the wind on T.G.I. Friday's "Wings and Things" special. In addition, the last thing you need is to have that 19-year-old intern drive you home because all he had was bar mix and diet soda. Embarrassing!

Tip #2: Don't Only Discuss Work

Without fail, you'll attend an office happy hour where you'll meet someone who can't stop talking about work. Of course you can discuss general work topics. "You were pretty swamped today. Everything all right?" A happy hour is also a great time to give kudos to a colleague on a job well done. "Walter, you really knocked it out of the park today with that presentation! Let me buy a drink." However, don't use the office happy hour as an opportunity to harp on an issue that went wrong or discuss the marketing strategies for next quarter. You'll have plenty of time to do that at the office.

The office happy hour is a chance to leave the worries and stress of the office behind and get to know your colleagues on a more personal level. No one wants to talk shop all the time, so use the happy hour as the time to mingle -- talk about family, movies, sports, whatever. Choose topics that show you have a personality and are not a corporate drone. Refrain from touchy subjects like religion, politics, and sexual orientation, and definitely don't comment on the status of someone's pregnancy body.

Tip #3: Don't Be a Wallflower

As I mentioned in the tip above, the office happy hour is a great way to learn more about colleagues on non-work level. However, this doesn't work if you sit back in your chair, with your nose buried in your smartphone, acting -- and looking -- like you can't wait for the event to end. If you don't want to be there, don't go. This isn't high school -- you don't get credit just for showing up. Instead, take advantage of talking to someone you rarely encounter at work. Or better yet, talk to your boss more openly. You might discover there is a real person behind that tough exterior.

Happy hour is a great way to network and learn about what your coworkers are up to (both in and out of the office). Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised about how fun someone is when they're not focused on deadlines or running to meetings.

I delve a lot more into the best ways to navigate the minefield of office life in my new book "Reply All...And Other Ways to Tank Your Career".

Still Writing

I've been waiting for Still Writing for a long time, ever since Dani first mentioned her new project to our class, sitting in her living room, surrounded by books. Oh, those books! Those books, alphabetized by author's name and categorized by type, over which my eyes glided so many times during the hours I was immensely privileged to sit in Dani's house as a member of her writing class. I learned more than I can possibly articulate from Dani and from my classmates during the 2 1/2 years I participated. I left Dani's workshop this past winter during a time in my life when I felt simultaneously overwhelmed by responsibilities and demands and painfully aware of how short my childrens' time at home was. I miss it, but I will never forget what I learned, and I know I'll be enriched for the rest of my writing days by my time in the class.

All of this preamble is to say: I'm wildly fortunate to be able to call Dani my teacher. Reading Still Writing felt like listening to Dani talk, and I can tell you first-hand that that's an immense gift. Still Writing is full of both specific ideas for and wise observations about the writing life, and it contains the kind of language that makes my eyes fill with tears and the kind of richness that I think about for days, weeks, and months.

At the outset of Still Writing, Dani asserts that "the page is your mirror" and quotes Emerson on how the good writer "seems to be writing about himself, but has his eye always on that thread of the universe which runs through himself and all things." These two images together remind us that every day a writer deals with the granular reality of him or herself and also with the largest questions of human experience. Still Writing does the exact same thing. Dani tells stories from her own life, both to show us how she came to be the writer she is and to demonstrate certain truths about the creative life. She also makes concrete suggestions which are pragmatic and thought-provoking in equal measure. Still Writing is studded with quotes from other writers and thinkers; by weaving these words with her own Dani both adds resonance to her narrative and affirms her place in the highest choir of those who write about writing.

The book is structured in three parts: Beginnings, Middles, and Endings.

Beginnings are about facing down our internal censor, about finding a place to sit that is a room of one's own, and of locating the "shimmer around the edges" that Joan Didion described. To begin is to find what Dani describes as a toehold -- whether that's character or place or dialogue or plot - and to release our need for permission. To write is to sit down, over and over again, to stay with something when it gets hard, not to look away. "The practice is the art," Dani reminds us. There is no avoiding doing the work. At the beginning it is also particularly useful to have a guide, and when Dani describes her first mentor, Grace Paley (to whom Still Writing is dedicated), I found myself nodding vigorously. As I read Dani say of Paley, "I often found myself on the verge of tears when I was in her presence," I was myself in tears. The fact is that's precisely how I felt about Dani when I first met her, and how I continue to feel. There are people who touch something deep inside us, in whom we recognize something kindred and also something to which we aspire.

Middles are about courage and quiet tenacity, about muses and finding the right early readers, about identifying the subconscious tics that fill our work and the inheritance and history that colors and shapes our writing, and about that monstrously difficult thing, structure. In this section Dani shares a line from Aristotle that I have heard her say in person more than once: "Action is not plot, but merely the result of pathos." She declares that "if you have people, you will have pathos" and goes on to say that for artists there is "no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others." The blessed unrest of which Dani speaks gives me that now-familiar sensation (because I've felt it many times when reading her work) of being known from the inside out, of someone reading my mind and putting it into words something I've felt but been unable to articulate. Yes. The pathos that we see, she is saying, is unavoidable, and though it hurts, we must keep seeing it and sharing it.

Middles is my favorite part of Still Writing. Dani urges us not to give up, to believe that "just at the height of hopelessness, frustration, and despair... we find the most hidden and valuable gifts of the process." I am in the middle myself -- of writing, of thinking, of life itself -- and her words encourage me more than I can articulate. "It has been said that the blessing is next to the wound," Dani writes in Middles, and I began to cry. There's no question this is true of me: my wound and my wonder are two sides of the same truth, of the frank astonishment at this world that is the lens through which I see every day. Again Dani describes something so true it sends a shiver up my spine:

I've learned that it isn't so easy to witness what is actually happening. The eggs, the cows. But my days are made up of these moments. If I dismiss the ordinary -- waiting for the special, the extreme, the extraordinary to happen -- I may just miss my life. It is the job of the writer to say, look at that. To point. To shine a light. But it isn't that which is already bright and beckoning that needs our attention. We develop our sensitivity -- to use John Berger's phrase, our "ways of seeing" -- in order to bear witness to what is. Our tender hopes and dreams, our joy, frailty, grief, fear, longing, desire -- every human being is a landscape. This human catastrophe, this accumulation of ordinary blessings, of unbearable losses.

Endings are about the "prickly, overly sensitive, socially awkward group of people" that form a writer's tribe (just that description alone makes me sigh with identification), the themes that "sharpen and raise themselves as if written in Braille," the necessity of telling our stories, even when it is hard, the fearful uncertainty of the business side of a career in writing, and the dangerous, seductive power of envy. It is also in Endings that Dani reflects on some of the grand themes of the writing life. It is in this section that we see most clearly that Still Writing is about more than writing: it is about living in this world, about paying attention, about honoring where we came from while recognizing where we are, about those we love and can trust and those whose intentions are less clear. It is about remaining open to the world, even - or maybe most especially - when it causes us pain.

Too often, our capacity for awe is buried beneath layers of perfectly reasonable excuses. We feel we must protect ourselves - from hurt, disappointment, insult, loss, grief - like warriors girding for battle. A Sabbath prayer that I have carried with me for more than half my life begins like this: "Days pass and the years vanish, and we walk sightless among the miracles.

We cannot afford to walk sightless among miracles. Nor can we protect ourselves from suffering. We do work that thrusts us into the pulsing heart of this world, whether or not we're in the mood, whether or not it's difficult or painful or we'd prefer to avert our eyes. When I think of the wisest people I know, they share one defining trait: curiosity. They turn away from the minutiae of their lives -- and focus on the world around them. They are motivated by a desire to explore the unfamiliar. They are drawn towards what they don't understand. They enjoy surprise. Some of these people are seventy, eighty, close to ninety years old, but they remind me of my son and his friend on the day I sprung them from camp. Courting astonishment. Seeking breathless wonder.

Still Writing is a book to read carefully and to savor over and over. I've read it twice myself already, and I know it will join books like Annie Dillard's The Writing Life in the pantheon of those volumes I trust most and revisit often. I'm fortunate and grateful to know Dani and feel sure that this volume, which contains so much of her wisdom, her heart, and her soul, will inspire passionate devotion in many, many readers.

This post originally appeared on A Design So Vast .

You can also find Lindsey on twitter, instagram, and facebook.

I Just Published My Grocery List on Amazon!

It's such an amazing thrill! The moment "My Grocery List" appeared on Amazon, I changed my Facebook job description from "Bolt Inspector" to "Published Author."

Thank you Amazon for making it so easy for ordinary people like me to become real, professional writers in less than an hour!

So far, the pre-publication reviews have been outstanding! Albertsons called it, "one of the best written grocery lists we've ever seen. The printing is excellent and, unlike most grocery lists, impressively legible. A must read!"

A bagger at Vons named Leticia opined, "I've found a lot of grocery lists that people leave in their shopping carts after they're done shopping, but Mr. Blumenthal's vivid combination of produce, canned goods and household products stands out as one of the most poignant and heartfelt lists I've ever read. I couldn't put it down."

Butch Milner, a checker at my local AM-PM store gushed about the book. "I loved the chapter called 'Bacon.' This book is destined to become a classic in the shopping list genre."

Just to give you a little background, I originally wrote the whole book with a Ticonderoga #2 pencil on the back of an envelope that once contained my gas bill. Like Hemingway, I wrote it standing up (in my case, in the kitchen.) And it only took me about two minutes!

The inspiration for the book was my wife Janet who had asked me to pick up a few things at Vons -- fifteen items in all -- because her sciatica was acting up. Once I got started writing, the words just flowed as if God Himself were guiding my hand. I didn't need to rewrite a single word, although I did cross out "2 Cans of StarKist Tuna" when Janet informed me that we already had a bunch left from our last trip to Costco.

Truth be told, I had kind of a hard time writing a plot synopsis for my Amazon page mainly because the book doesn't actually have a plot. Also, the actual writing is limited to just a few words (brevity is the soul of wit, right?) and a lot of blank space. But I had to write something so I came up with this description: "'My Grocery List' is the heartbreaking story of a diverse family of grocery store items tragically separated by long, brightly-lit store aisles. They lead lonely, barren lives, shivering in the store's arctic air, knowing that soon they will all be swept up in the crazy adventure of the conveyor belt and the soulless scanner. Eventually, their lives will intertwine climactically when they're confronted by the poignancy and eroticism of commingling in my cloth bags."

(Of course, none of that stuff is actually in there -- you have to imagine it all. I like to leave interpretation to the reader.)

In the rest of my synopsis, I described the tempestuous love affair between my two protagonists, "Seedless Grapes" and "Yoplait Low-Fat Yogurt." Then there's a nonexistent subplot about my jaunty, lovable character, "Windex Extra-Strength" who sits on a rack all day staring longingly across the aisle at the beautiful, soft and sexy "Downy Fabric Softener," who only has eyes for the powerful but villainous cad, "Dulcolax Laxative Tablets."

But I really shouldn't tell you any more. I wouldn't want to spoil it! You'll just have to find out for yourself by reading the book. I've priced it at $2.99. Those with short attention spans will be glad to know it's a quick read.

In the meantime, stay tuned for my next book, "A Few Things I Need at the Hardware Store."

Ayn Rand Had a Sense of Humor; Her Followers Don't!

On one particular afternoon I had arranged for her to be interviewed by Barry Farber on WOR Radio in New York City. She was to meet me at the Times Square studio at 5 pm. The one thing I could count on was that Ms. Rand was never late. Until this particular afternoon. She was stuck in a titanic traffic jam and since those days were pre-cell phone there was no way she could let me know. It was left to me to appear on the show as her substitute. Let me just say that I was philosophically opposed to most everything Ms. Rand stood for. "I live in a world of grays, of faults and indecisions," I started out, "a world where doubts and imperfections co-exist with kindness, empathy and generosity of spirit. Compromise does not have to be a nasty word, much as Ms. Rand wishes otherwise. Civilization depends on people caring for one another." With every word, the hole I was digging myself deepened. This she did not know until she heard the interview on her car radio. When we finally spoke later in the evening her only comment was that I had a very good radio voice. Nothing else. My inner voice warned me that the best/worst was yet to come.

A few nights later we had dinner at the Playboy Club for which I also did publicity and that, to my initial surprise, Ms. Rand found most interesting. For the first time she asked about the work I did, how the Bunnies were hired, trained, treated by management, etc. By the time I finished I jokingly said she could now take over my job. Who could have planned that at that very moment I was told that a group of Italian journalists were in the lobby asking for information about the Club. "That will be fine," said Ayn (by this time she insisted I call her by her first name), rising from the table to head me off. "Good evening, gentlemen" she greeted them, edging me aside. "My name is Tania Grossinger and I'm on the public relations staff. Welcome to the Playboy Club. I'd love to give you a tour. Did you know, incidentally, that in order to keep their job, each of the Bunnies has to sleep with the boss?" She then went on to describe Hugh Hefner as a sexual pervert and misstated everything I had told her earlier. I stood there like an idiot. "And you should see the parties that go on upstairs after the Club closes. If you're not busy later, perhaps..." By that time she had only to look at my face to know she had punished me enough and started to laugh. "I'm sorry to disappoint you lovely gentlemen but as I hope you have figured out by now, I don't really do not do public relations for the Playboy Club and I'm not Tania Grossinger." She invited them to join us for a drink where she explained that I had recently caused her some chagrin and their arrival provided her the perfect opportunity to surprise me as I had surprised her. At least I can say I had the last word. Would the journalists like to know who their "guide" really was? "Don't you dare," she said. I dared. So the writers left with an unexpected bonus. In addition to interviews with two Playboy Bunnies they also had one with the famous Ayn Rand. Alas, to their dismay, no invites to the 'party' upstairs!

How many readers would associate Ayn Rand with a sense of humor? Knowing the somewhat harsh persona she projected, would anyone even believe my story? That was the challenge I faced when I had to decide whether or not to include the above anecdote in Memoir of an Independent Woman; An Unconventional Life Well Lived. I couldn't imagine anyone would be upset with what I wrote, certainly not in context of everything else I wrote in the Playboy section where I shared a personal side of Ayn Rand that few had been fortunate enough to see. I was wrong. I received multiple emails from acolytes who said they knew Ayn Rand would never have set foot in a Playboy Club therefore nothing else I said about her could be true. I was accused of demeaning the seriousness of everything she stood for. One person even suggested I was lucky he couldn't get his hands on me.

What did I learn from this? I learned that something as innocuous as a person having a sense of humor is going to offend someone, that devotees often have trouble looking past first impressions and, what I've known all along, one can't please everybody all of the time. The response to that particular section also reminded me that its good to periodically stir readers' juices.

Ayn Rand for sure would have chuckled!

How to Find a Book in the Future

When he and I took driving trips up and down the coast, we would arrive in town early enough to visit the bookstores in Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Santa Cruz and San Francisco. We spent hours exploring the shelves and finding treasures. There was the year we discovered Calvino. The year we started reading Alice Munro. The year I found Anne Carson. The year he found Ben Marcus. At those bookstores, you had the intersection that every writer wants to see. You have the reader/young intellectual in a space where there are books, and there is the cashier ready to take your money. That's all you need: Reader, books, money in reader's pocket, cashier. The transaction is complete.

Where is that transaction happening now? My daughter is 23, finishing her Masters in English. Where is she, a young intellectual, going to discover books? Her kind of books. We all have our kind of books, but we read diversely. I bought a Malcolm Gladwell book at the airport, but I also love novels, adore poetry, am a big fan of short stories. Most of us read off different shelves. What makes most people want to buy a book for pleasure is picking it up, holding it, turning the pages, feeling the cover, smelling that new book smell. We've come to substitute hearing about a book, and then ordering it from Amazon. But when you receive the book, there's that pleasure of opening it, turning the pages.

There's another problem with finding your book. When we buy music or listen to music, we have iTunes or Pandora to tell us what we might like. I call my Pandora, Nina Simone radio and they fill me with in with who else I might like. That's what iTunes does as well. According to Bill Tipper at Barnes and Noble, what Netflix does is different because it is based on your continuing to rate what kind of movie you like. What Amazon does is even less helpful because it's based on book buying which can sometimes be random. You might buy lesbian erotica and cookbooks, but that isn't going to be true of everyone. I edited a book, Devil's Punchbowl, a collection of essays on California. It's taught at a number of different universities so when you look on Amazon, it will tell you that if you like it, you might like the grammar book Rules for Writers as well. When I look up Margaret Atwood, it doesn't tell me to buy other post apocalyptic novels like her later books or other feminist books like her early books, instead it tells me that I might like other books by Margaret Atwood.

There was a time when I enjoyed going to the Barnes and Noble on Ventura Boulevard. They had a great fiction selection, and the staff were helpful. Not as much poetry as I would have liked, but it was a good store. Now there's not a Barnes and Noble or an indie bookstore in easy driving distance. My students still give me Barnes and Noble gift cards, but there's no place to go with them except BarnesandNoble.com. I continue to like five things about Barnes and Noble:

1. They keep stores open in key cities. Maybe because they're a big enough corporation, they can afford some ups and downs.

2. Those bookstores create a meeting place for book lovers. According to Everlasting Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, one of my favorite movies, it might be a place book lovers can meet other book lovers and after the store closes, head off for some recreation with that like minded individual.

3. They are much easier to work with than Borders ever was. Borders' business practices left much to be desired.

4. They have a website which creates a conversation about books. If you want to read key conversations with exciting new writers, I highly recommend BarnesandNoble.com. There are reviews and recommendations based on curating by educated readers rather than a buying algorithm.

5. They are creating a way of buying books that gives you ideas of what else you might like. That's because the people choosing the comparable books are people. They read and they know what they like and what you might like. It's like that shelf at your favorite bookstore that gives you staff picks.

I'm going to take out my magic spyglass and tell you about the future. In the future, ebooks won't be sold on Nooks or Kindles. The reason is that we only want one device in the future or at most two and the one should have the capability of being a toy. We would prefer one device. If two, one will be an iPhone/Droid, the other will be an iPad/ tablet. I think we'll have tablets which will be cheap, and can be used for watching movies, listening to music, playing games, reading books and the newspaper and magazines, and, well, everything. We don't want to have three devices. A laptop/pad, a phone and some sort of e-reader is really overload.

I don't think the end product is going to be an Apple product. My students tell me that the reason Droids are better than iPhones is that they come jail broken and you have to jail break an iPhone. But that's not the main reason. The reason I wouldn't bet on Apple products is that I don't think Apple likes their customers. But don't believe me, read CNN's ten reasons to hate Apple.

The big conversation about books we will like is happening online hence the popularity of sites like Good Reads and Bookslut. Those conversations will continue and many of them will lead to the purchase of real books. We'll still have books and hammocks to read them in. As an editor, I want readers to be able to find our books, and I hope the conversation becomes more active and more focused so we can find the books we love, the ideas we want to swim in, the language we want to speak. It's complicated to predict the future. We all want to live in interesting times, and indeed it is the best of times and the worst of times. I walked into the Barnes and Noble office this morning and thought about where the book universe was going. Barnes and Noble is a tenant in the Google building.

Why ABCs Matter As Much As 123s

That which is measured, is managed

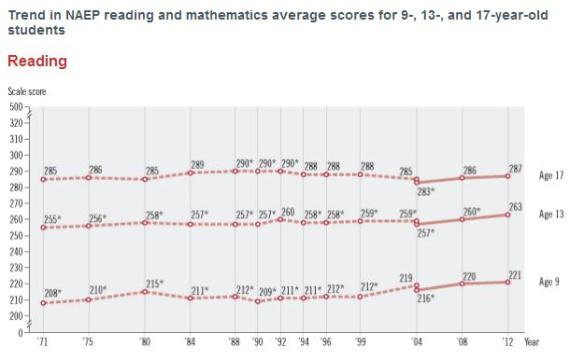

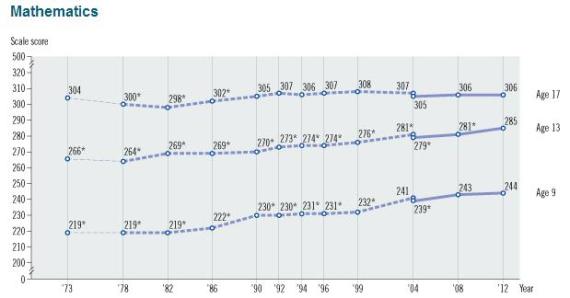

The U.S. media is saturated with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) coverage, constantly focusing on the importance of education in science and mathematics - and parents, children and schools have responded. In fact, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress' "Nation's Report Card," the average math score for 9-year-olds was 25 points higher in 2012 than in 1973, compared with only a 13 point increase during the same period for reading. Why should we care about this gap?

The link between reading and creativity

According to a recent study published in the journal of Learning and Individual Differences, children with well-developed reading skills were found to have enhanced creative abilities. Researchers found that higher reading scores were associated with higher scores in creativity. Reading is critical in developing balanced children who are creative and social as well as analytical, yet parents and educators alike are regularly bombarded by the media about U.S. scores in math and science versus other industrialized nations.

The case for more creative leaders

An IBM survey of more than 1,500 CEOs from 60 countries and 33 industries worldwide found that creativity was believed to be the most crucial factor for future success - more so than rigor, management discipline, or integrity. The results showed that IBM CEOs felt many of the challenges they are confronted with could be overcome by instilling creativity in an organization. When we hire at MeeGenius, we weigh creativity heavily in a sea of intelligent, analytical candidates. If our children are the future leaders of tomorrow, perhaps we need to consider the strong link between reading and creativity and why they are so important for building critical thinking and leadership skills.

So, how do we get there?

Experts agree - reading gaps that exist before kindergarten are very difficult to overcome in later years, which is why it's imperative that we start early. Sean F. Reardon, a professor of education and sociology at Stanford, found that there is a large disparity in school readiness tests among children from wealthy and poor families when they enter kindergarten, and this gap grows by less than 10 percent during school years. He also notes there is evidence achievement gaps narrow during the school year, and then grow again during the summer. So how can we help combat the inadequacy of early childhood readiness?

The answer will be driven by technology. Even in other categories this is true. If we look at Math, for example, technologies like Khan Academy, which offers free 24/7 tutoring online, exist to help develop our children's skills further. In my home, we see reading as part of the daily routine, like bathing. Try to make reading a habit and not a chore.

When I ask my friends about books, we can all agree that we each have a library of them sitting in our child's bedroom (I, too, like the feeling of having a hard copy in my hands), but when I'm not at home, my iPad serves as a reading partner that can articulate new words and open new doors for my children. Our product research, conducted by an outside digital agency, found technology can be a great complement to parental reading. Word highlighting and read-to-me narration allows young children to focus on the words, rather than the illustrations. The research also found books are read 37% faster by a caregiver versus a professionally narrated book on MeeGenius. We hear so much negativity regarding children's screen time, but this research showed technology slows down the reading process.

The ask.

As cliché as it sounds, change doesn't happen overnight. To Parents: I urge you to start reading early and often. Make the most out of the devices you already have. To Media: the next time you write about STEM or the 13-year old mathematician, think about making your next story about a reading prodigy who's changing the world. To educators: Discuss with parents the importance of reading with children outside of the classroom.

The Magic of a Novel

There are probably several reasons why a novel can grab and hold you so you're sorry the read is coming to an end.

First, there's the story itself. It resonates on some level. It taps into something deep within you -- perhaps the situation in which the protagonist is placed, or the twists and turns of the plot fire up your imagination and spur you on to the next page -- and the next. It may be the child's wish, residing in each of us, to know what happens next? Plot matters greatly and shouldn't be underestimated.

Equally important are the characters populating the novel. You want to care and feel for the protagonist. It matters what happens in his or her life. If he feels fear, you have that feeling. If she feels lust, so must you. If he's in a jam, you want to sweat along with him. If she feels devastated, you want to feel her anguish. In other words, you want to identify with the character and be inside his or her head and heart while the person negotiates the rigors of the plotline.

The novel must tap into some universal (yet personal) experience. It must reach out from the page and clutch onto some human commonality that exists for all of us. When a novel resonates deeply, it's usually because you can say I've felt that way... exactly that way. When that happens, the author has succeeded in capturing you into the world of his imagination.

Of course, there's language and dialogue. Dynamic language can describe so much while telling a story. It provides richness, and the scene comes alive. You can see, hear and even smell what's on the page.

When a writer's dialogue is crisp and real (think Elmore Leonard) you can actually hear the characters. An old saw has it that dialogue isn't just what people say to each other, it's what they do to each other with words. Each word spoken in a novel can connote action, or intention; and add to the story's narrative drive, it's arc... its essence.

People have preferences formed by their individual natures, backgrounds, and cultures. A good novel can transcend these differences and transport you to another world. It can make you live there and experience what that world is about (think of the Harry Potter novels, The Hunger Games or Game of Thrones).

Artfully written, a novel can make you leave behind your world -- at least for the hours you spend reading -- and enter the one unfolding on the pages before you.

Now that's magic.

Rhode Island Education Commissioner Deborah Gist Skydives For Literacy

Last year, the principal of a Rhode Island elementary school ate a worm after the school’s students met their reading goals. This year, state education commissioner Deborah Gist went skydiving after students at Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy (BVP) won the state’s summer reading challenge.

Gist jumped out of a plane on Saturday with BVP’s math and data coordinator, as the school had highest percentage of students in the state complete all their summer reading goals, according to a press release. The stunt was pulled in an effort to support literacy.

Dozens of students and teachers watched Gist and teacher Drew Madden jump out of a plane in Middletown, R.I. Gist says she now would recommend skydiving to anyone.

“It happened fast, so you really didn’t have time to think or get nervous,” she told the Providence Journal.

To see Gist skydive for literacy, watch the above video.

Can books help a small child to understand what is real?

There are plenty of walking, talking toys in children's books - but a good storyteller can breathe life into a blue kangaroo or a box of crayons without pretending they are living beings

My four-year-old has just begun asking questions about "real" and "not real". Is her soft toy Snowdog real? Are there any stories about toys coming alive that can help her to understand this?

The classic example of a story in which the author opening breathes life into an inanimate object is The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams, which charts the journey of a soft toy rabbit from being just one a bunch of nursery companions to something superior. It was written in 1922 and subtitled "How Toys Became Real", and one of the reasons for its enduring success is that the eponymous velveteen rabbit is itself anxious to discover what 'real' is and how you can become it. Margery Williams gives several definitions of what the word might mean.

Early on, the Rabbit asks the Skin Horse, a long term resident of the nursery cupboard, "What is REAL? … Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?"

"'Real isn't how you are made,' said the Skin Horse. 'It's a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.'"

Almost a century on this explanation will probably seem too saccharine and too obviously untrue, although the book remains in print, especially in gift editions with its stunning original William Nicholson illustrations.

To avoid this untruth, authors now draw on the child's attachment to a much loved toy and belief in the special powers it holds as the way in which it can seem real without a false transmogrification.

In Rumor Godden's magical The Fairy Doll, a little girl believes that the fairy can help her overcome her lack of confidence. She wishes and, as importantly, the Fairy Doll wishes too: between them they create a magic which enables the one to help the other although they only communicate through wishes.

Similarly, in Emma Chichester Clark's Blue Kangaroo stories the connection between Lily and her soft toy companion gives him such an active role in the stories that he seems like a real play friend. In Where Are you, Blue Kangeroo, the kangaroo gets sufficiently anxious about being lost to take matters into his own hands. By hiding in the toy cupboard he avoids running the risk of being left on the bus – an experience he did not enjoy.

Throughout children's books, from the Gingerbread Man onwards children learn that the unreal can, for the purposes of a story, come alive.

Oliver Jeffers does this brilliantly in his most recent book The Day the Crayons Quit, in which each of the colours in a box of wax crayons writes its own polite but firm letter to their owner complaining of how he uses them! Maybe, through books such as these, your daughter will learn to appreciate how much-loved "things" can be brought to life through stories even if they can never become living beings.

Book doctor is always on hand to answer your questions or track down that book for you. You can reach her by email via childrens.books@guardian.co.uk

A Love Letter To New York City

1. The city, was what people from New Jersey called it. The city, as if there were no other. If you were a suburban Jewish girl in the late 1970s, aching to burst out of the tepid swamp of your adolescence (synagogue! field hockey! cigarettes!), the magnetic pull of the city from across the water was irresistible. Between you and the city were the smokestacks of Newark, the stench of oil refineries, the soaring Budweiser eagle, its lit-up wings flapping high above the manufacturing plant. That eagle—if you were a certain kind of girl, you wanted to leap on its neon back and be carried away. On weekend trips into the city, you’d watch from the backseat of your parents’ car for the line in the Lincoln Tunnel that divided New Jersey from New York, because you felt dead on one side, and alive on the other.

2. At least once or twice a month, when I was in high school, I’d slip out of third-period algebra. No one noticed. I’d walk a mile to the train station in Elizabeth and board the 11:33 to Penn Station. The windows were gray with the film of cigarette smoke.You could write your name on them. The train car, largely empty. The men who worked downtown had long since commuted, and the women tended to drive or stay home. Some of my friends’ mothers had never even been to the city. It was the end of the 1970s. I was fifteen, and not a soul knew my whereabouts. I disembarked in Penn Station and made my way through its urine-stained halls in my corduroys and Fair Isle sweater, trudging along in my Wallabees. North up Eighth Avenue, past strip joints, neon XXX signs, bodegas. I stopped when I reached Lincoln Center and took a moment by the fountain in the plaza, looking at the Chagalls framed by the arched windows of the Metropolitan Opera. Hungry, I continued north to 72nd Street, where I spent my allowance on a turkey, tongue, and coleslaw sandwich and a Dr. Brown’s CelRay soda at the Fine & Schapiro delicatessen. I imagined that I was already a woman, that I had shed Jersey, my extreme youth, like a layer of baby fat. By the end of the school day, I’d be back home, delivering monosyllabic answers to the question, “How was your day?” But secretly, I was high on the knowledge that I had done it. I had been there.

3. In a popular TV commercial of that era, for Charlie perfume, an actress named Shelley Hack strode across the screen in her pantsuit, blonde mane flying. She was the Charlie girl—tall, urban, glamorous, on her way to important places—someone who was “kind of now, kind of wow, Charlie,” as the jingle went. She had it all—and why not? With the hubris of the very young, I planted both feet in my fantasy. I was the Charlie girl. My life in New York was going to involve some sort of career in which I could wear pantsuits like that.

4. I moved to New York at nineteen, into the West 75th Street walk-up apartment of a boyfriend. The boyfriend owned a small shop on Columbus that sold South American artifacts and the peasant clothes popular with a certain urban-bohemian crowd. My father—an Orthodox Jew—threatened to disown me if I shacked up (his words) with my boyfriend. So I married him. It seemed like a fine solution. We divorced a year later. But in between—as a college student—I threw dinner parties in that brownstone apartment, making the one dish I knew how: Chicken Marbella from The Silver Palate Cookbook, with olives, prunes, and cinnamon, flavors I haven’t liked in combination since. In photos from that time I see a round-faced girl with feathered hair (hello, Farrah), dimples, and a ring that had no busi- ness being on her finger. Our block was home to several dancers from the New York City corps de ballet whom I’d see heading to re- hearsal early in the mornings, their heads small and neat, their long necks wrapped in soft scarves. I made the mistake of thinking that we were alike, these dancers and I, because we were the same age. But in fact, they were moving toward life, and I—masquerading as a happy homemaker—was drifting away from it.

5. “Kind of now, kind of wow, Charlie.” Another one of the Charlie girls was an actress named Cheryl Ladd, who went on to be one of Charlie’s Angels (no relation). And then there was a model, Shelley Smith, whom I would meet many years later—in another life, a future I couldn’t possibly imagine—after she had opened an egg donation agency in Beverly Hills and I was trying to have a second child. But back then, to me, she was part of a trifecta of blondes who epitomized life among skyscrapers—a burnished, free-floating glamour that seemed, in itself, a worthy goal.

6. Divorced and twenty. How many people can claim that? For years, I erased that marriage from my life story. It was just too hard to explain—to others, to myself. But now, thirty years later, I wish I could reach back through time and shake some sense into that lost little girl. I wish I could tell her to wait, to hold on. That becoming a grown-up is not something that happens overnight, or on paper. That rings and certificates and apartments and meals have nothing to do with it. That everything we do matters. Wait, I want to say—but she is impatient, racing ahead of me.

7. The city. It isn’t possible for me to write about the city without writing about real estate and men. From the baby-marriage, I moved on to a full-blown affair with an older married man. From a walk-up on 75th, I graduated to a duplex in the West Village and finally to an apartment on the top floor of the Dakota. The Dakota apartment looked like a dollhouse, with a string of tiny rooms, slanted ceilings, walls papered with peach and lavender Laura Ashley flowers. I ate next to nothing and drank white wine and frozen margaritas. I drank champagne with my girlfriends at Petrossian, and we charged our drinks to our parents’ credit cards. I had my nails done next to Madonna, my hair blown out next to the original uptown girl, Christie Brinkley. I took back-to-back aerobics classes at Bjorkman and Martin, a cultish studio run by a compact woman with powerful thighs named Lee who taught us intricate dance steps and yelled at those who couldn’t follow. When the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded over Cape Canaveral, we—all of us drenched in perspiration at that studio—held hands and said a prayer.

8. There were other apartments, other men. Chance encounters, coincidence, desires, and invitations. Another brief, failed marriage. All before I was thirty. I was trying, flailing, failing, in an attempt to chisel myself into a woman who existed only as a fantasy, airbrushed, photoshopped, as lost as that high school sophomore who wandered in a fugue state past the strip joints of Times Square. I was a girl who hadn’t gotten the memo about not taking candy from strangers—and New York was full of those strangers. A girl who was playing a part she was wrong for, whose own gifts were elusive and strange to her, contraband, brought home from a foreign country and best stored out of reach.

9. But still, all the while, I was becoming a writer. How to explain this—how, without conceiving myself as a split screen, one part of me blurry and undefined and the other honing skills, finding the words, becoming, in the invisibility, the solitude of these rooms, these apartments, someone with something to say. I wrote my first novel, then another. I began to teach. I interned at a literary magazine on 17th, lugged home laundry bags full of manuscripts, and sat cross-legged on my bed as if mining through coals for gold. I went to book parties in clubs and smoky bars and had them thrown for me. I lunched on vertical salads with my terrifying agent at Michael’s on West 54th Street, where table position determined pecking order, and no one was ever quite focused on their own dining companion. Wasn’t that Barbara Walters being shown to the window table? I posed for a portrait in Vanity Fair in a tiny lemon yellow suit, my hair big and fluffy, a face covered in makeup, in a coffee shop on West 83rd Street. Once, late at night, as I was in bed reading manuscripts, a giant water bug flew across the bedroom and landed on my shoulder. I screamed and called the doorman, a man who must have been in his late seventies, who poked with a broom through the shoes and boots littering my closet floor until he found and disposed of it.

10. I could lecture on metaphor; I could teach graduate students; I could locate and deconstruct the animal imagery in Madame Bovary. But I could not squash a water bug by myself. The practicalities of life eluded me. The city—which I knew with the intimacy of a lover—made it very possible to continue like this, carried along on a stream of light, motion, energy, noise. The city was a bracing wind that never stopped blowing, and I was a lone leaf slapped up against the side of a building, a hydrant, a tree.

11. I am writing this from a small study in a house high on a hill in the Connecticut countryside, two hours north of the city. It is winter. The bare branches of wisteria that climb our roof are banging against the window. One of my dogs is curled up at my feet. I hear the sharp pitter-patter of the other as he forages through the house for crumbs left from a party we threw the other night. The walls of my study are hung with photographs: My son as a ring-bearer at a friend’s wedding, tiny in his first tuxedo. My husband, from his years as a war correspondent, lighting a cigarette in his flak jacket on a rooftop in Somalia—a reminder that he, too, had a life that he left behind when he met me. While I was drinking champagne on my parents’ credit card, he was filing stories from the bloody streets of Mogadishu.

12. It has been ten years since we left the city. A decade—long enough for our friends to stop taking bets on how long it would take us to come to our senses and return to New York. What do you do up there? Whom do you see? What’s it like? They drive up to visit us in their Zip cars or rental SUVs, bearing urban bounty: shopping bags from Citarella filled with pungent Epoisses and chorizo tortellini; boxes of linzer cookies from Sarabeth’s; delicate, pastel Laduree macarons. In turn, we take our houseguests on hikes or to lakeside beaches or to quaint village streets lined with shops selling cashmere and tweed. But we aren’t hearty country folk. I don’t own muck boots or a Barbour coat. We don’t ski or own horses or build bonfires in our backyard. I spend most of my days alone in my writing study, with a midday yoga break in the next room. My husband now writes and directs films, and the closest he gets to an outdoor activity is when he takes his chainsaw out into our woods to clear brush. Our son, like us, is an indoor dreamer. We are urban Jews, descended from the shtetl, pale and neurasthenic. Living in our heads.

13. Deep within my recesses there is a turntable, its needle skipping, skipping. My twenty-year-old self, straight from Jersey, watches me, hands on hips. How could you? she accuses me. When we’d come so far? I want to tell her that we were refugees, my husband, son, and I, fleeing north, heading away from a place and time that we hoped would recede, like the view from our rearview mirror, until it disappeared entirely, until it became nothing more than a memory. I want to tell her that my baby had been very sick. That my father was dead, my mother dying. That we watched as one plane, then another, crashed into the towers, debris swirling in the sky above us like a storm of blackened snow. That everything I thought I knew about living no longer applied. That the champagne and the men and the real estate and the book parties were like the fool’s gold that my now-teenage, healthy son unearths on his geology field trips. Look, I want to say. This life you think you want is a shiny apparition. Those restaurants and clubs, those bars bathed in a light pinker than sunset? Those cafes where photographers from magazines took your picture, and makeup artists dusted your pretty nose? They will be submerged, as in a shipwreck, the seas of time washing over them until something new has taken their place. The joint where you now drink those frozen margaritas will become an organic juice bar. The bistro with the best steak frites is now a T-Mobile store. The bookstore where you will eventually give your first reading sells boxes of hair dye and curling irons. It all changes—even institutions, even concrete towers, even, or perhaps most of all, our very selves—my foolish little sweetheart. That’s how I could leave. Trust me. You’ll thank me someday.

14. I am not yet old, but I am no longer young. My city—the one that beckoned just beyond the smokestacks and Budweiser plant—has vanished. Only glimpses of it remain, in the sandstone facade of a Fifth Avenue building, or Washington Square Park, when seen from a certain angle. My city broke its promise to me, and I to it. I fell out of love, and then I fell back in—with my small town, its winding country roads, and the ladies at the post office who know my name. I did my best to become the airbrushed girl on its billboards, but even air-brushed girls grow up. We soften over time, or maybe harden. One way or another, life will have its way with us.

15. I still drive into the city once a week or so. I see doctors, get my hair done, have lunch with my agent, have dinner with a girlfriend at a candlelit restaurant where we share a bottle of wine and order the cheese plate. I give readings from my books in crowded, East Village bars. If I can, I squeeze in a yoga class near Union Square, in a loft filled with plants and statues of the Buddha. Mostly, I watch the young people—their new designs in facial hair, piercings, and tattoos—who are in the midst of their own love affair. They’re from Ohio or Nebraska. Or New Jersey. They’ve arrived, and they’re here to stay, just as I once was. It’s their city now. I have become invisible to them. I could be their mother. They laugh and whisper, lovely heads bent together. Sometimes, if it’s going to be a late night—the theater, perhaps, or a boozy dinner party—my husband and I stay over at a hotel. We pull up to the entrance in our SUV with Connecticut plates, a middle-aged couple from out of town, just as my parents once were. “Can I help you folks get a taxi?” the doorman asks. “Do you need directions?” No, my husband tells him. That’s okay. We’re from here. We know our way around.

This Book Spotlights the Design Geniuses at Apple (Not Named Jobs)

Thin Reads: Your magazine Fast Company is the gold standard when it comes to covering innovation in the world of business. Would you say Apple is the most innovative company in its time? As far as innovation, where does it stand as far as U.S. companies over the last 100 years?

In it's time, I'd say almost certainly: yes. Over the past 100 years, I think the question gets tougher, especially when you're comparing PCs, which Apple popularized, with innovations in medicine, transportation, and agriculture that have changed the world in ways that are arguably far more sweeping. I think innovations like container shipping and the modern factory may have had a bigger impact on the world than PCs.

Thin Reads: A fascinating undercurrent throughout Design Crazy was how dire Apple's fiscal health was in the 90s in contrast to the dominance of Microsoft. How the tables have turned two decades later. What lessons can Apple -- and indeed all companies -- learn from this turn of events?

I think the most important lesson is that good design can trump pretty everything else. I know that Steve Jobs and the Apple faithful would have strenuously disagreed, but once reason Microsoft came to dominate personal computers in the mid-90s was that Windows 95 was simply better than the Mac OS; and Windows PCs were better than Macs (and the Mac clones offered for a fleeting moment).

Apple turned the tables in the end because it created a series of products--most importantly OS X and the early iMacs--that were better designed than what Microsoft and the PC manufacturers offered. (The dominance that Apple achieved was the result of a two other products: the iPod and iPhone, which helped convince people to abandon Windows PCs.) Especially in the case of the iMac, these products weren't always innovative--the iMac, as you'll learn from the book, was basically one of Apple's junky beige box computers with a pretty case--but they were well-designed. They weren't conceived as a series of engineering specs, but rather as distinct products. That was something new, and I think it's what made the difference.

Thin Reads: The book mentions the lack of mobility for many Apple executives. Do you think this is a possible threat to the long-term health of Apple?

The Apple structure is effective as long as Apple executives feel like they work for the most important company in the world -- for a company, as one former Apple designer put it to me that is "Florence during the Renaissance." That's a powerful feeling that matters more than any promotion. Would you care about being promoted to middle-management if you thought you were working for the Leonardo of the modern era?

The trouble will come if Apple's product line stagnates, which could create an exodus of talent that is more severe than in traditionally managed companies. If Apple falls, it will fall hard.

Thin Reads: Explain how you were able to corral so many Apple employees to speak on the record about their experiences at the company. You and your collaborators must have extraordinary powers of persuasion.

Apple is notoriously secretive and, as I've been told, pretty ruthless with employees who leak. The funny thing is that, while our sources seemed legitimately afraid of Apple, they shared their stories readily -- and in most cases without hesitation. They gave us so much of their time, and with such generosity.

When the Fast Company editors first suggested the idea of an oral history of Apple design, I think I actually gasped out loud. It's one of those stories that simply wants to be told.

Letter: Robert Barnard steered the Brontë Society through some quite stormy times

Robert Barnard was a creative force in the endeavours of the Brontë Society, based in Haworth. A member of its council and chairman for many years, he encouraged and contributed to academic research into the works and lives of the Brontës while ensuring that the interests and enthusiasms of the less professionally engaged were catered for. After steering it through some quite stormy times, in the end he guided it safely into port. He will be much missed; the success of the society's activities today is largely due to him.

Letter to an Older Feminist Who Happens to Be Named Phyllis Chesler Who Happens to Be My Mom

Thanks, we are all feminists now.

In the final letter of your 1998 book, "Letters to a Young Feminist" -- the letter that you addressed to me -- you requested that I send you postcards from the future. This is not a postcard but we are in the future and I am writing to you about feminism.

I have always self-identified as a feminist. And that's because you were one; it was family tradition. Over the years I made a conscious choice to embrace feminist principles.

But, mom, now I truly get it. I understand who you are and how you became a leader of women. It has all come together in your latest book, An American Bride in Kabul, in which you tell us your feminism origin story. Rather than gaining your powers from a radioactive spider or gamma rays, as with other superheroes, you were forced to come face to face with woman hatred. You faced becoming the property of your ex-husband and his family in Afghanistan, a place where, because you were a woman, you had no rights. You faced gender segregation and apartheid. You faced Jew hatred, forced conversion, and woman's inhumanity to woman, at the hands of your former mother-in-law. You survived violence and rape. And, then you survived death after contracting hepatitis. For all these reasons, too, I am a feminist.

You may not know this but feminism is everywhere. In the so-called feminist blogosphere, which is inhabited by both men and women, feminism and women's lives are debated by the second. Grassroots feminist social media campaigns against sexism and misogyny have been have successful. Some say this is the Fourth Wave of feminism.

There are debates online about whether to use the term intersectional feminism. Or womanism. Others prefer to consider themselves humanists or egalitarians. There are also debates about whether male decline is a myth, and whether the patriarchy is dead, and whether men can be feminists. Still others are discussing where feminism went wrong, for example, by promising women personal perfection. Or, by failing to include women of color. Or, by failing to include men. Others are discussing why women can't have it all, whether women need to have it all, or even how we should define "all."

Whatever people may call themselves, we all care about these issues because of the feminist movement and its teachings. In a poll taken earlier this year, while only 20 percent of respondents considered themselves feminists, 82 percent of respondents believed that "men and women should be social, political, and economic equals." Unfortunately, many people who believe in feminist values refuse to call themselves feminists because feminism is still a dirty word. Public figures, celebrities and high-level professionals -- from Lady Gaga to Beyonce to Marissa Mayer -- have refused to embrace the term. We need to reclaim it. Because, as the singer Ani Difranco has noted, one is either a feminist or a sexist; there is no other choice.

I am a feminist because as a man it is painful to see society devalue my mother, my wife, my daughters, and my female friends. I am a feminist because patriarchal rules limit and dehumanize men too, replacing genuine human emotions with violence and anger.

More recently, I am a feminist because I have daughters. So, I worry about rape and sexual assault and violence and sexual harassment. I worry about whether they will be able to control their bodies. I worry about eating disorders and depression. I worry about the sexualization of young girls. And, I worry that they will be judged by their appearance and not the content of their character. And worse -- that they too will judge themselves this way.

The failures of feminism are no reason to resist the label. We should simply be improving on the ideas of our feminist foremothers. The actress Ellen Page said it best: "How could it be any more obvious that we still live in a patriarchal world when feminism is a bad word?" And, as the late Andrea Dworkin explained: "Feminism is hated because women are hated."

I, for one, do not care if the term "feminism" is palatable for all. It is the only appropriate word for those that believe in the radical notion that women are people who should be equal to men, but also that women are entitled to self-determination in everything from their bodies to their roles in the public and private spheres.

MOM: I thank you for telling your origin story. I thank you for surviving Kabul. I thank you for birthing me and becoming a mother of the women's movement. And, I thank you for teaching me to love women.

I call myself a feminist too. I accept the role of Amazon Knight, and will carry your words into battle with me, along with a banner bearing a scarlet letter F.

Love,

Your son, Ariel

P.S. Happy birthday both to you and "American Bride." May you both inspire us all to fight for women everywhere.

More than half of American adults read books for pleasure in 2012

The good news: According to a new report from the National Endowment for the Arts, more than half of American adults read books for pleasure in 2012. The bad news is that the percentage of adults reading works of literature -- in the NEA's definition, novels, short stories, poetry or plays -- has declined since 2008, returning to 2002 lows.

via Books - latimes.com http://feeds.latimes.com/~r/features/books/~3/gb1cuK6UfJk/la-et-jc-american-adults-read-books-for-pleasure-in-2012-20130930,0,6200116.story

Tips, links and suggestions: What are you reading?

Are Self-published Authors Really Authors or Even Published?

The topic of self-publishing, which I include to mean both printing one's own books and paying a so-called vanity press, is one that generates heated debate about its place in the literary marketplace. On the positive side, self-publishing has freed frustrated book writers from having to scale the mostly impenetrable fortress known as the book industry and bypass those who hold the keys to the castle, namely, literary agents, editors, and publishers.

The fact is that a few self-published books have had great success and the authors have since received contracts from established publishers, for example, Amanda Hocking, who has sold more than 1.5 million copies of her self-published books, and E L James, the author of the Fifty Shades trilogy. Additionally, established authors, including David Mamet, have chosen to self-publish has a means of gaining more control over their works and keeping more of their profits. Many famous authors started out self-publishing their works including John Grisham, Jack Canfield, Beatrix Potter, and Tom Clancy.

Here's a factoid: Twelve publishers rejected J.K. Rowling's first Harry Potter book before she found a relatively small publishing house (Scholastic isn't small any longer!) willing to give her a chance. And you know how she's done since! There are, I'm sure, many great works of literature that have not seen the light of day because of the myopia of the book industry. And self-publishing gives those works a chance to shine.

At the same time, the self-publishing industry has allowed anyone with a computer and a small amount of money to call themselves authors. Not long ago, I read a fascinating article in The New York Times (unfortunately, I haven't been able to find it when I did an Internet search) that questioned whether self-published authors should be called published authors. Rather, the article suggests, they are book writers who have their books printed. There is, I believe, a significant difference between authors published by traditional houses and self-published books in that the latter lack the processes that we can count on to ensure a minimal level of quality, both of content and style.

The publishing houses are certainly not beyond reproach as judges of worthy literature. There are many books published by the houses that are critically panned and sell few copies. Yet, despite their warts, the publishing industry does serve a valuable role as an initial arbiter of literary quality (however flawed it may be). Books that are accepted by a genuine publisher go through a rigorous (though obviously imperfect) multi-layer vetting process that includes an agent, an editor, several outside reviewers, an editorial committee, a sales and marketing committee, and often the publisher him or herself.

What process does self-publishing typically go through to ensure quality? Well, of course, the authors themselves write multiple drafts until they are satisfied. But you know how objective authors are about their own works. Then perhaps they have a relative or friend edit their manuscript (that's what I did), another source of dubious objectivity and literary good judgment.

There's no doubt that calling yourself a published author isn't what it used to be. But, to be fair, being published by an established publishing house doesn't ensure that you wrote a quality work or that it will be a critical or sales success (I can speak to the latter point!). And being self-published doesn't mean that you wrote a work of vanity. As someone who has both published and self-published, I believe that there is, however, a difference.

And self-published book writers seem to know too. Whenever I meet someone who tells me they are an author, I always ask who their publisher is. If they hem and haw, I know they self-published because they also know that their state of authorhood lacks a certain legitimacy that comes from having a traditionally published book.

I don't begrudge book writers having their books printed. They should be rightfully proud of the effort required in writing a book. As a friend of mine once said, many a Great American Novel never found its way to paper (or screen, these days). Anyone who is willing to sacrifice the time and incur the opportunity costs of writing a lengthy manuscript should be admired. Far be it from me to extinguish the flames of an impassioned writer.

And someone has to write the next great work of fiction or nonfiction; why can't it be John, or Maria, or Ken. And what if the publishing industry misses its chance? Self-publishing provides a venue to those missed opportunities to find their place in the marketplace of ideas.

But, however wonderful that scenario sounds, it is not very likely. To put self-publishing in perspective, self-published books rarely ever find a place in brick-and-mortar bookstores and they get buried in the websites of online booksellers like amazon. And about 99% of self-published books sell only a few hundred copies at most, so even if the next work of literature is self-published, it still will probably not ever be discovered.

The only thing I know for sure is that the rules of publishing are changing. Will self-publishing ever attain the legitimacy of traditionally published books? At this point in its evolution, no one can tell. But until self-publishing has proven itself, I'm going to argue that there is a difference publishing and self-publishing and between authors and book writers.

The art of the letter finds a modern home

What started out as novelist Jon McGregor's blog has been turned into a journal dedicated to handwritten submissions

The Royal Mail is to be sold off and Twitter will float on the New York Stock Exchange, but the art of long-hand letter writing is being celebrated in one corner of the literary world: The Letters Page is a new journal whose first edition is out on Wednesday.

The journal is edited by the novelist Jon McGregor, and emanates from the School of English at the University of Nottingham, where he is writer-in-residence. The first issue includes letters from Magnus Mills, the UK's most famous novel-writing bus driver, whose 1999 debut, The Restraint of Beasts, was shortlisted for the Booker; and 2013 Booker-longlisted novelist Colum McCann.

Mills' handwritten letter read:

Dear J,

Sorry I didn't reply sooner. Thanks for asking and I'm really very flattered, but I don't think I'll be able to supply a hand-written letter for the collection …

McGregor and students from Nottingham's creative writing course are reading and selecting the letters for publication. In a footnote to Mills' piece, McGregor wrote: "We are unclear whether the use of a handwritten letter to apologise for there being no handwritten letter is a deliberate or fortuitous irony. Either way, it's an irony we appreciate."

McGregor won the Impac prize in 2012 for his novel Even the Dogs, about an alcoholic who dies at Christmas; and his debut, If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things, was longlisted for the Booker prize in 2002 when he was just 26.

The idea of taking letters as the primary form for a journal grew from correspondence he had with prospective writers and readers about what they wanted from a new literary publication. McGregor requested that handwritten letters were submitted by post, many of which initially formed a Tumblr blog, The Letters Page.

"Letters are one of the earliest forms of writing, and are quite a big part of literary culture and history. They're like a [vinyl] record or a piece of handwriting, they're valued as distinct. I don't say that if you write longhand it will be better, but the tools you use affect the way you think about what you say," McGregor said. This year, he has attempted not to use email, writing long-hand letters instead. "It was kind of a coincidence and fed into my thinking for the journal."

Colum McCann, who also won the Impac prize in 2011 for his novel Let the Great World Spin, writes of "the greatest letter I ever received":

Dear Reader —

Great letters, like great novels, remind us where we were. I could patch my life together with old airmail papers. The greatest letter I ever received was from my literary hero, John Berger (2), a letter that arrived, blue, out of the blue. He is a beautiful letter writer (3). Sometimes I can hear his pen glide across the page.

McCann's footnote explains: "(2.) John often writes notes in his letters, along the side. I always think: 'Never again will a single story be told as if it were the only one.' [The quotation is from G, the 1972 Booker Prize-winning novel by John Berger.]"

Upcoming editions may focus on letters from prison, letters of complaint or thank-you letters, and "even letters to Jimmy Savile. There must be a whole generation who wrote with their requests", McGregor said, adding "it would have to be handled sensitively".

The Letters Page is published three times a year and is distributed free as a downloadable PDF. Submissions are open for the second edition, on the subject of penpals, until 16 October.